Minimally invasive abdominal and visceral surgery

Reflux disease | Bariatric surgery for weight loss | Inguinal hernias | Further treatments

Minimally invasive surgery is the umbrella term for conservative surgical techniques with specially developed cameras, optical devices and instruments. Such operations are gentler and less stressful on the body since a wide opening of the body cavities is not necessary. These operations are frequently referred to as endoscopic or laparoscopic operations. This includes the mirroring of the internal organs concerned (e.g. the abdominal organs): using a camera introduced into the abdominal cavity, the operative field can be made visible on a screen. The procedure is performed with the aid of special surgical instruments through small skin incisions.

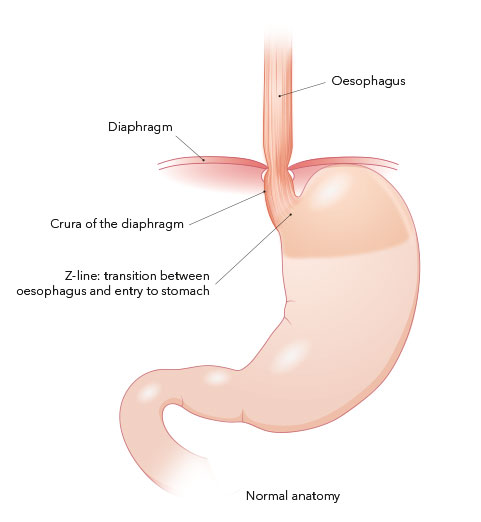

If the closure mechanism at the exit of the oesophagus to the stomach is too weak (known as cardia insufficiency), acid and other stomach contents as well as bile increasingly enter the oesophagus. The mucous lining of the oesophagus has no protection against the acid. This causes problems such as acid reflux or a burning sensation behind the sternum.

The exact causes of reflux disease are not known. However, the main reason is insufficient closure where the oesophagus exits into the stomach. It is known that this concerns a connective tissue weakness, which can be either congenital or, more frequently, acquired. Another cause can be an inadequately functioning oesophagus that is unable to react quickly and strongly enough to return the acids to the stomach when they enter the oesophagus (this also happens occasionally in healthy people). Furthermore, certain “exogenous factors” are also partly responsible: chronic nicotine and alcohol consumption, for example. Obesity also leads to raised pressure within the abdomen and can have an influence. Reflux disease often occurs in combination with a hernia of the diaphragm. However, this is not essential for the development of reflux disease. Likewise, a hernia of the diaphragm does not necessarily lead to reflux disease.

Symptoms of oesophageal inflammation

Acid reflux and a burning pain behind the sternum are clear signs of reflux disease. Further symptoms can include nausea and vomiting, back-flow of stomach acid or food remnants up to the throat or mouth area (especially when lying down or bending over) with coughing, accidental ingestion, burping and pain in the upper abdomen. If the symptoms occur more frequently or over an extended period of time, this is then defined as chronic gastrooesophageal reflux disease. The symptoms often do not correlate with the severity of the oesophageal inflammation (“oesophagitis”). Thus a severe inflammation can be present which causes only minimal discomfort, and vice versa. In the most severe cases (known as Barrett’s oesophagus), there is an up to 10 percent risk of the disease becoming malignant within 10 years and that a life-threatening oesophageal cancer develops. Such symptoms should therefore always be investigated, then treated and monitored if required. Around 25 percent of people in the West will suffer such symptoms at least once.

If the problems have persisted for longer than two to three months, imaging of the oesophagus, stomach and upper section of the small intestine should be performed (known as panendoscopy). However, further investigations are required, such as measurement of the exposure to acid and of the pressure ratios in the oesophagus. These examinations can be performed as an out-patient and are not stressful. They can be used to determine the severity of any mucosal inflammation in the oesophagus. The motility and strength of the muscles of the oesophagus are also assessed. Any over-acidification of the oesophagus can also be examined. These findings are very important for any surgical treatment of the reflux disease.

Conservative therapy

The primary treatment of reflux disease is always conservative. This is generally made with medications which reduce or block acid production in the stomach. This usually treats the oesophageal inflammation and classic symptoms very well. A relatively large portion of the population regularly takes such medications (particularly proton pump inhibitors), often for years or for life. A change of diet and loss of weight also often lead to improvement of the symptoms (e.g. early and light evening meals, slightly raising the head of the bed). However, the conservative, non-surgical treatment of reflux disease only addresses the symptoms; the cause remains.

Surgical therapy

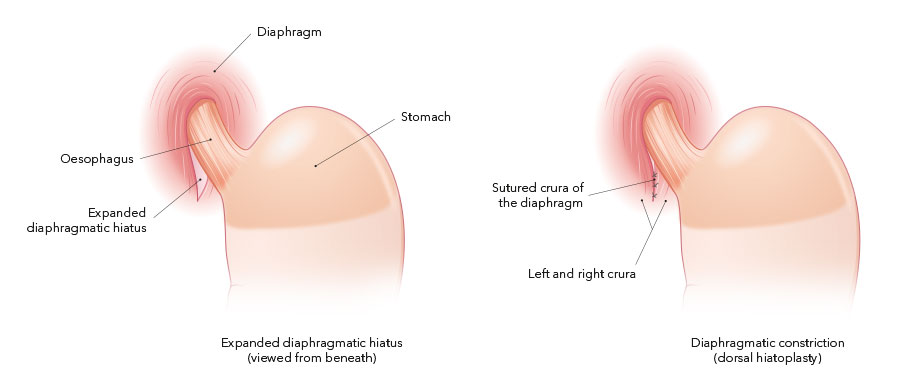

The goal of surgical treatment is a secure closure between the oesophagus and the stomach. This can be achieved in part by restoring the normal anatomical conditions (reduction of the hole in the diaphragm and correction of any hernia present) and in part through the additional formation of a small stomach sleeve, placed like a collar around the lowest section of the oesophagus. This strengthens the transition between the stomach and oesophagus and prevents the back-flow of acid and stomach contents into the oesophagus. The advantage of the surgical therapy is that the reflux symptoms generally disappear completely. Medications are no longer needed and the mechanical problems which underlie the disease can be definitively corrected.

BICORN procedure

Surgical treatment without sleeve construction exists in the so-called BICORN procedure (Biological Conservative Reconstruction) according to Ablassmaier. We have slightly modified this procedure in our centre through the additional fixation of the oesophagus, re-stretched during the operation, in its position. The modified BICORN procedure with simultaneous tension-free fixation of the oesophagus to the bilateral crura of the diaphragm (oesophageal cruropexy) has been our standard procedure for more than four years, not least also because of the extremely low rate of complications and side-effects. In contrast to the procedure with a sleeve construction, after a modified BICORN operation patients can expel air (burp) and also vomit, if need be. So-called gas bloat syndrome, observed very frequently during operations with a sleeve construction, practically never occurs.

The BICORN operation modified by us means that the upper half-moon shaped portion of the stomach is once again in its correct position after the operation. Due to the simultaneous decrease in size of the enlarged diaphragm hiatus and the stretching and fixation of the oesophagus, the normal anatomy and physiology in this region is restored. The pump function of the oesophagus is improved. This simple procedure prevents an abnormal reflux of acid and stomach contents in the long term.

Bariatrics addresses the causes, prevention and treatment (conservative and surgical) of obesity. Our centre has provided surgical treatment options since 1996 for morbid obesity, its consequences and accompanying diseases (e.g. diabetes, high blood pressure, metabolic disorders, sleep apnoea, joint problems, etc.). The precise cause of obesity is still not known. It covers a highly varied collection of symptoms. Factors which appear to be involved in causing morbid obesity include genetic (inherited) and hormonal factors, environmental factors, the metabolic situation, the extent of physical activity and nutrition.

Bariatric surgery is varied and constantly developing. Different surgical procedures are thus used accordingly: these either lead to limiting food consumption (= restriction), reducing the uptake of nutrients (= malabsorption) or a combination of both procedures.

Gastric bypass surgery

Gastric bypass surgery is now one of the most common procedures for severely overweight patients. This substantially changes the anatomy of the gastrointestinal tract. There are two forms of gastric bypass operations which completely differ in their principles.

Proximal gastric bypass surgery

The classic standard procedure massively reduces the stomach volume (to approx. 10-15 ml). A new connection is made between the small remnant stomach and the upper part of the small intestine, allowing food to flow. This new connection is known technically as an “anastomosis”. In proximal gastric bypass surgery, the anastomosis is deliberately made narrow to restrict the amount of food eaten. Similar to a gastric band and gastric sleeve surgery, this is a restrictive procedure.

The transectioning of the stomach requires the gastric, bile and pancreatic fluids to be rerouted to a lower section of the small intestine. The common ileum portion of the small intestine then has 2.5-3.5 metres for nutrient utilisation and absorption (including caloric uptake). This procedure initially leads to good weight loss. Unfortunately, a considerable portion of these patients then start to regain weight after a few years, slowly, but surely. We do not know why this happens. It is assumed that the body becomes accustomed to the low calorific uptake and hormonal switch (enterhumoral factors); even a tiny increase in calories (in whichever form) is then enough to put on weight again. For patients who regain weight after proximal gastric bypass surgery, we adapt the proximal bypass into a distal gastric bypass using laparoscopic (keyhole) enterotransposition. This is a minor procedure in which the stomach, bile and pancreatic fluids are redirected into the small intestine at a much lower site. This leads to strongly reduced nutrient uptake (malabsorption) such that the patients have long-term weight reduction again even when eating normally.

Distal gastric bypass surgery

In distal gastric bypass surgery the stomach is also reduced in size but, in contrast to the proximal form described above, the new connection between the small remnant stomach and the small intestine (anastomosis) is deliberately not made narrow. Food intake is thus barely restricted or not at all. Furthermore, the stomach, bile and pancreatic fluids are diverted much lower (distally) along the small intestine. Digestion, the breakdown of different nutrients (especially fats) and thus the uptake of calories, only begins there where the food mash mixes with the bile fluids. This is therefore not a restrictive procedure, but a malabsorptive procedure. The food which is eaten is only processed and used to a small degree. Many patients appreciate the fact that they do not need to alter their eating habits drastically. The fact that fat digestion only begins in the lower small intestine means that undigested fats reach the large intestine. There is no uptake of calories here. Rather, water is reabsorbed from the stool to thicken its consistency. For patients with a distal gastric bypass, this means that excessive fat intake is largely passed undigested into the large intestine and excreted the natural way as a fatty stool. Fatty stools are characterised in that they contain a lot of fat (as the name suggests), are often fluid to very soft and, primarily, highly odorous. Fatty stools cannot be fully eliminated with a fat-reduced diet, but they can be substantially decreased.

Intermediate gastric bypass surgery

The intermediate gastric bypass is a "weaker" variant of the classic distal gastric bypass. From a technical perspective, it is fully comparable with a distal gastric bypass. The loss of weight is slightly less than the classic distal gastric bypass, but fatty stools practically never occur. Here also the loss of weight is not as rapid as with classic distal gastric bypass surgery; this is certainly an advantage for the skin which needs to adapt. We perform this procedure primarily in patients without an excessive BMI (usually below 40 kg/m2), who are not targeting an “ideal” weight reduction and who do not wish to have fatty stools.

Gastric sleeve surgery

Standard gastric sleeve surgeries have been performed since 2006. This is a relatively new surgical procedure, hence long-term results are not yet available but the short- and mid-term results are excellent. Gastric sleeve surgery represents a very promising alternative to the other surgical procedures.

In this procedure, which is performed laparospically (keyhole surgery), the volume of the stomach is reduced from the normal 1,000-1,500 ml to around 60-120 ml by removing the outer portion of the stomach. The remaining stomach resembles a sleeve which reaches from the entry of the oesophagus to the stomach exit. This is a restrictive procedure. Food consumption is thus massively reduced and the feeling of satiety is reached quickly, with a positive effect on calorie uptake. The biggest advantage compared to the gastric band is the absence of a narrow section in the upper part of the stomach. Food is not then simply held up and back, but flows unimpeded into the (very small) gastric sleeve. However, the extreme reduction of the stomach leads to a very rapid sensation of fullness. Gastric sleeve surgery substantially reduces the size of the portions eaten. In addition, the removal of a large part of the stomach (especially the upper section, called the fundus) reduces the production of an appetite-stimulating hormone. Ghrelin (growth hormone-release inducing) is a “hunger hormone", primarily formed in the stomach. The level of ghrelin in the blood rises when hungry, stimulating the appetite. The levels fall again after eating. The extensive reduction of the stomach thus also reduces ghrelin production. This has the positive effect that the feeling of hunger is reduced overall and the feeling of satiety is reached quickly.

As with all surgical procedures for weight reduction, regular medical follow-ups are essential. Furthermore, certain dietary rules must be observed. Only very few calories should be consumed in “liquid” form (sugary drinks, chocolate, ice cream, etc.) as these reach the small intestine almost without restriction and can be metabolised there. This can lead to renewed weight increase. For those who are not prepared to reduce their consumption of sweets drastically (or not for the long-term), gastric sleeve surgery as a therapy option is neither appropriate nor likely to be successful.

Laprascopic mini-gastric bypass

As well as surgical techniques proven over many years, we have also recently started performing another surgical procedure for long-term weight loss for severely obese patients. This is known as a laprascopic mini-gastric bypass (LMGB) and has been used for some years at various international centres with great success. LMGB is a combination procedure, consisting of a restrictive component (smaller portions of food owing to a reduction of the stomach resembling a gastric sleeve), malabsorption (the food consumed is utilised poorly, thus fewer calories are absorbed from the intestines) and so-called enterohumoral factors (hormones which influence the uptake of certain nutrients via the stomach-small intestine passage over the long-term). Thus it contains components of gastric sleeve (restriction), proximal (restriction and enterohumoral factors) and distal (malabsorption) gastric bypass surgeries. It is one of the few bariatric procedures which is reversible.

From a technical perspective this is a comparably simple procedure routinely performed laparoscopically. In contrast to classic gastric bypass surgeries, only one new connection between the stomach and the small intestine is created (the other gastric bypass surgeries create two new connections). This surgery is thus suitable for extremely overweight patients at high risk, as well as in the event of a re-operation for patients with gastric sleeves.

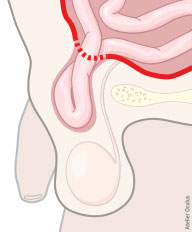

Inguinal (groin) hernias are among the most common surgical problems. They affect men nearly nine times more often than women. Inguinal hernia is generally treated with surgery. In most cases, hernias are annoying and cause few to no symptoms. Despite this, there is always the risk that an inguinal hernia will become trapped (or strangulated). This is because there is a large risk that the trapped parts will no longer be supplied with blood and can die within a few hours. When parts of the intestines are affected an inguinal hernia can be life-threatening, even today.

Cause and anatomy

The exact cause for the occurrence of inguinal hernias has not yet been determined. It is known they occur more frequently within some families and that there must be a certain connective tissue weakness (congenital or acquired). Inguinal hernias are therefore to be considered as an illness. These connective tissue weaknesses also commonly lead to varicose veins, haemorrhoids or hiatus hernias of the diaphragm. The cause for why men are more frequently affected by inguinal hernias than women lies in the fact that the testicles develop in the rear section of the abdominal cavity and then migrate down the inguinal canal into the scrotum. The spermatic cords (testicular vessels and vas deferens) run from the testicle through the inguinal canal back into the abdominal cavity. Hence the canal is never fully closed in men and represents a weak point of the anterior abdominal wall. The inguinal canal can expand under some circumstances (e.g.chronic coughing, constipation (pressing), sport, etc.), which can lead to an inguinal hernia over time. There are various types of hernia possible in the groin (direct and indirect inguinal hernias, femoral hernias, obturator hernias, etc.). It would be too difficult and complicated to go into detail about the different types of hernia in this brief publication.

Symptoms

The main symptom is one or more large swellings in the area of the groin which increase in size when pressing (coughing, sneezing, carrying heavy loads, etc.) and which then usually spontaneously disappear. There can also be pressure pain, or wrenching or burning sensation. The pain can also occasionally radiate into the area of the testicles or upper thigh. Many patients only notice an inguinal hernia by accident. They mostly feel a lump in the groin when showering and consult their doctor to investigate further. Whether someone feels few or even no symptoms is usually independent of the size of the hernia. Indeed it is often the small hernias which cause the problems as these are more likely to lead to strangulation events. Inguinal hernias occur on both sides in approx. 15 to 20 percent of cases. If an inguinal hernia causes strong pain and cannot be pushed back into the abdominal cavity by hand, this is an emergency situation. This usually requires immediate surgery.

Diagnosis

In most cases, the suspected diagnosis of an inguinal hernia can already be made after a detailed examination of the medical history. The subsequent physical examination then usually confirms the finding. In rare cases, the diagnosis of an inguinal hernia cannot be made with certainty with a simple examination (e.g. for severely obese patients). In these situations, an ultrasound examination of the groin can be useful. This requires a great deal of experience and should only be performed by doctors who perform this procedure frequently. Alternatively, an MRI of the abdominal wall can also provide information for the diagnosis of an inguinal hernia. However, this examination is very expensive.

Fig. 1: Inguinal hernia with herniation of parts of the intestines through the inguinal canal.

Therapy

Inguinal hernias can still only be definitively corrected with surgery. Patients who do not wish to undergo an operation or who cannot do so for health reasons should be treated with a hernia truss. This provides external compression to the weak point of the musculature in the groin and prevents the herniation. However, such a procedure is only justified in absolute exceptions. The aim of the surgery is to reposition the hernia sac and its contents at the anatomically correct site and to close off the hernia gap safely and without tension. There are several surgical procedures for closing a hernia. In adults, we have been using an endoscopic method for over 25 years which is viable and extremely safe in most patients. This is the TEPP (endoscopic Totally Extraperitoneal Preperitoneal) method. We clearly favour this technique for the treatment of practically all inguinal hernias (except in childhood). A camera is inserted via a 12-mm incision in the navel between the abdominal musculature and peritoneum. With video-endoscopic control, further, smaller 5-mm incisions are made in the skin to the left and right of this. The surgical instruments are fed through these. These accesses are enough to correct an inguinal hernia (including bilaterally) surgically with a mesh (or two meshes for a bilateral hernia). The gaps and weak points in the muscles are not sutured, but closed without tension using a specially developed mesh. These are inserted into the space between the peritoneum and the abdominal muscles and fixed there with clips or glue. This surgical method has several advantages over other procedures: only the smallest incisions are required which are later practically invisible (cosmetically excellent), the abdominal cavity is not opened and the hernia gaps can be closed without any tension. After the surgery, most patients have little pain and the rate of a hernia recurring (relapse) after this procedure is below 0.1 percent. The procedure lasts from 20 to 50 minutes for a unilateral hernia, to 30 to 90 minutes for a bilateral hernia. Surgeons who offer the TEPP method must have performed at least 300 to 400 operations to be proficient in this technically difficult procedure. The hospitals stay after a TEPP operation is usually one to two days at most. You are able to carry loads directly after the surgery, depending of course on the symptoms.

Author: Mischa C. Feigel, M.D.

- Gall-bladder surgery

- Rectal surgery (haemorrhoids, anal fistulas, fissures, rectocele, rectal prolapse)

- Colon surgery (diverticular disease, tumours, appendicitis)

- Surgical treatment of abdominal adhesions

- Spleen surgery